Mastery over space

A Paper by Jason Crawford

Starting with the first passenger railroads around 1830 through the deployment of passenger jets in the 1960s, powered vehicles have dramatically shrunk travel times, at all scales, from the neighborhood to the world. Yet we are still limited by distance. It matters enormously what city you live in, because it’s expensive and time-consuming to travel outside of it; even within a metro area, people are limited by commute.

Increases in speed and convenience don’t just save us time: they expand our world, as we begin to take trips that were inaccessible before. Across a wide variety of societies and transport systems, from rural African villages to modern US and Singapore, people spend about an hour a day on total travel.²⁵ So when speed doubles, rather than cutting our travel time in half, it instead doubles our travel radius, opening up more of the world to us—and since area goes as the square of the distance, doubling a travel radius actually opens up four times as much of the world.²⁶

The next great frontier in speed is supersonic passenger flight. At the speed of Mach 1.7 planned for the airliner from Boom Supersonic, you could fly from New York to London in under 4 hours, or San Francisco to Tokyo in 6 and a half.²⁷ This possibility was proven more than 50 years ago with Concorde; it has merely been languishing for want of updated technologies and a profitable business model.

Passenger jets, however, will always have the problems of trains, buses, and other forms of mass transit: they go from station to station, not from your origin to your destination; and they come and go on their schedule, not yours. The ultimate in travel convenience is a personal vehicle: one that leaves whenever you’re ready, starts from wherever you are, takes you wherever you’re going, and lets you stash all your stuff in the trunk. In the bold, ambitious future, we might create transportation that combines the convenience of personal vehicles with the speed of air travel: the “flying car.”

Like most people, I was initially skeptical of this idea, seeing it as a fantasy of science fiction. I changed my mind after reading J. Storrs Hall’s Where Is My Flying Car? Hall recounts the history of flying car research and development, catalogs design approaches, models engineering tradeoffs and travel times, and concludes that there is no technological or economic reason why we can’t have flying cars with existing technology.²⁸

The vehicles of the future might also be autonomous—a huge boost to convenience, cost, privacy, and safety. Already, self-driving robotaxis are doing business on the streets of San Francisco, Los Angeles, Austin, Atlanta, and Phoenix.²⁹ Early data shows that Waymos are far safer than human drivers—unsurprising to anyone who’s taken a ride in one and noticed how mild-mannered its driving style is. Flying cars might also need autonomy, for safety and to obviate turning everyone into pilots. And autonomous trucking might reduce the cost of freight by over 40%.³⁰

But all of the above is just about getting around Earth. Sooner or later, it will be time to make a serious foray into space.

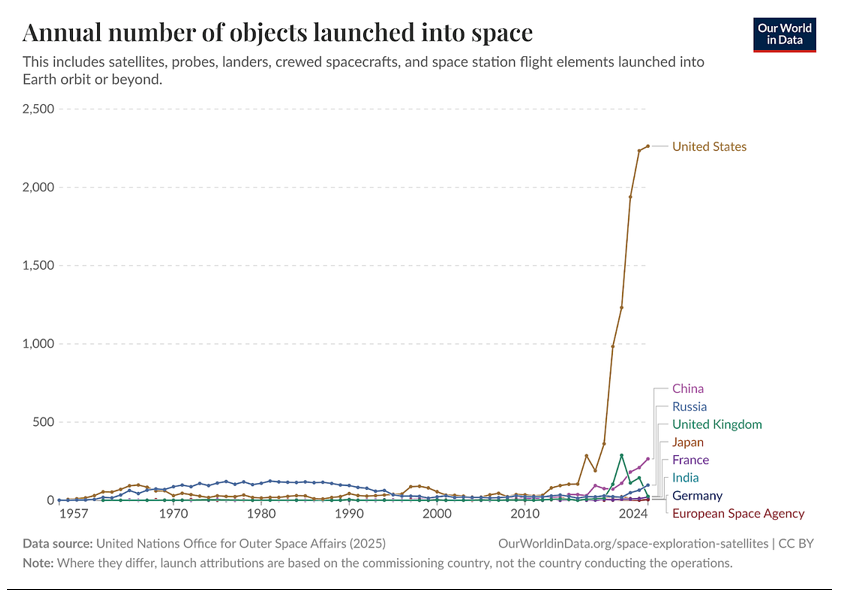

Rocketry, after peaking during the Apollo program and languishing thereafter, is finally advancing again in recent years, mostly thanks to SpaceX. After decades of launch costs hovering around $10,000/kg, Falcon 9 lowered costs to $2,600/kg and Falcon Heavy to $1,500/kg.³¹ This has driven more than a 20x increase in the annual number of objects launched into space. Many of them are Starlink satellites providing high-speed internet service to air passengers, rural homes, van-lifers, fishing boats, oil rigs, scientific outposts, disaster zones, and battlefields.³²

For Starship, the aspirational long-term target launch cost is $10/kg, which would expand the space economy even more dramatically.³³ But by that point, they might face competition from other launch providers—such Longshot Space Technology, which is making enormous cannons that use pressurized gas to shoot cargo out of the atmosphere.³⁴

The economic case for space is sparse right now. The best reasons to go beyond Earth orbit are tourism, science, maybe asteroid defense, and some just-emerging applications of space manufacturing.³⁵ Other applications, such as space-based solar power or mining the Moon or asteroids, don’t seem to be economically useful in the foreseeable future.³⁶ Some factors will inevitably push us into space if growth continues—at some point we will exhaust something on Earth, whether material resources or energy or heat dissipation³⁷ or simply room for more people—but those limits are orders of magnitude away.

Still, space calls to us. In his famous speech on the Moon mission, John F. Kennedy invoked the British mountaineer who had wanted to climb Mt. Everest “because it’s there,” saying: “space is there, and we’re going to climb it.”³⁸ I suspect that as soon as we can afford the luxury, we will go to space because we want to, for the sake of exploration and adventure, well before we have to for reasons of economics